Fresh Kills 2024 Movie Review

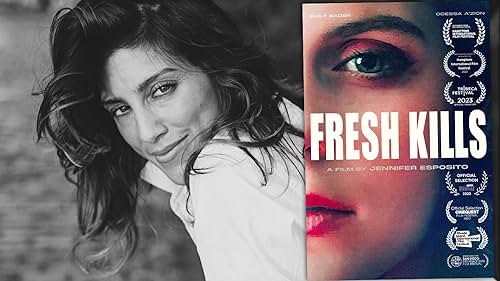

Mob narratives seldom place women front and center, unless it’s in a flat-out comedy (“Married to the Mob,” recent “Mafia Mamma”) or campy TV movies like “Mafia Princess” and “Bella Mafia.” No stranger to the genre as an actress, Jennifer Esposito attempts to balance that ledger with her debut as writer-director, “Fresh Kills.”

This solid drama centers on a family not unlike “The Sopranos,” but with its patriarch mostly pushed to the background. The focus here is on wives and daughters, who must turn a blind eye to criminal doings from which they both benefit and suffer the consequences. Originally a Tribeca premiere, “Fresh Kills” has been traveling the festival circuit and should prove a viable item for streaming platforms and broadcasters.

After a framing sequence that fast-forwards to a later moment of crisis, we meet the Larussos in 1987 as they’re moving on up to a “better life” from their old Brooklyn one, taking over a fairly palatial Staten Island address. This upward mobility doesn’t do much to quell the volatile marital chemistry between Joe (Domenick Lombardozzi) and Francine (Esposito), or fundamentally change their two children, with Rose remaining the “quiet one” while Connie is her brash opposite.

As the two girls become young women played by Emily Bader and Odessa A’Zion, those characteristics only deepen — Rose’s passivity makes her easily pushed around by everyone, in particular her hotheaded sibling. “You are part of this family whether you like it or not,” she is told, and any whiff that she may not like it incites furious lectures from “Con” about family loyalty, sometimes accompanied by a physical threat. When Rose hints she might want something more than engagement to neighbor Bobby (David Iacono), or managing the bakery her father bought to keep Connie and troubled cousin Allie (Nick Cirillo) “out of trouble,” she’s given an angry earful of “Ya think ya bettah than us?!?” Even the mother who treats her as a confidante doesn’t want her getting any notions of independence.

These characters don’t really evolve, or get revealed as more complex than they first appear; Esposito’s screenplay has authenticity but not a lot of depth or surprise. Still, her relatively narrow focus is well-served by performances and direction that fill it out with lived-in assurance.

Despite the title, “Fresh Kills” is an organized crime tale whose body count and violence remains largely offscreen. What grips us is the fear that those things might at any moment invade the domestic lives depicted, and the resulting tension that suffuses everyday doings. The denial Rose has lived in — naively asking wised-up Connie “Is Dad an honest man?” — eventually collapses in the worst way possible. Even then, however, the emphasis isn’t on dirty deeds done, but the compromises these women make (knowingly or otherwise) to accommodate them. They married into being, or were born as, accessories.

In the showier of the two lead roles, A’Zion convinces with a scary volatility that makes Connie roughly equivalent to James Caan’s “Godfather” part, or De Niro’s in “Mean Streets”: the explosive live wire whose recklessness seems to invite doom, though her fate isn’t quite as anticipated. Bader carries the film ably enough, even if Rose could have used a little more elaborating of the intelligence we’re meant to assume she possesses (like more than her one big idea being to try out for a job on Sally Jessy Raphael’s TV show.)

She gets an accusatory climactic speech that feels a bit forced, as does one just prior for the always welcome Annabella Sciorra, who’s otherwise underutilized as a supportive aunt. Esposito herself is fine as the simultaneously dissatisfied and resigned Francine, though the suggestion of real mental instability in one early sequence goes unexplored. Lombardozzi and the other male cast members are effective, however few glimpses are given into their money laundering, murders and whatnot.

Professional rather than particularly distinctive in its stylistic aspects, the production makes its most assertive aesthetic impression via production designer T.V. Alexander’s garish decor (Francine fancies herself talented in that regard), plus the big hair and loud fashions of the late-’80s/early-’90s era. The film could have had more fun with vintage cuts on the soundtrack, settling for some rather weak covers of Radiohead and others. But overall it evokes a highly specific milieu with finesse, eschewing cultural caricature.