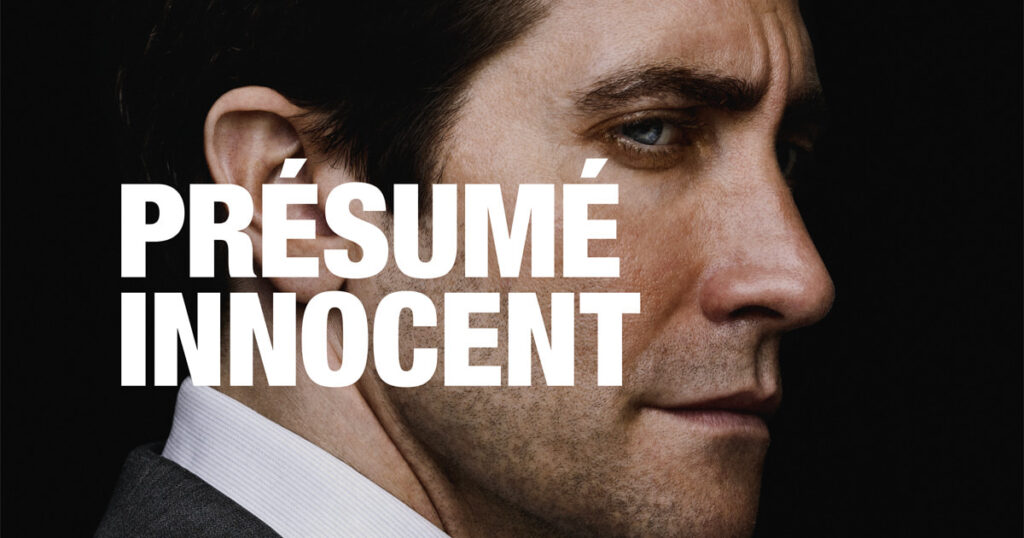

Presumed Innocent Review 2024 Tv Show Series Cast Crew Online

In its lean two-hour runtime, Alan J. Pakula’s 1990 adaptation of “Presumed Innocent” makes a number of incisive points about the American judicial system. First and foremost, it questions whether a courtroom is where truth is ascertained, or merely where various facts are tossed about until a version of the truth satisfies the controlling parties. (Roger Ebert clocked pessimism from the film’s opening shot, which, paired with Harrison Ford’s glum voiceover, suggests a pervasive hopelessness for all involved. “As he speaks of the duty of the law to separate the guilty from the innocent, there is little faith in his voice that the task can be done with any degree of certainty.”)

Each fallible, failing step in the process of trying a man for murder is given enough of a nudge to amplify the viewer’s unease, be it ingrained biases of supposedly neutral adjudicators, political influences dictating an individual’s freedom, or the sexist assumptions inherent to yet another patriarchal American institution. What’s left, in the end, isn’t just a climactic verdict for the accused — and a juicy reveal outside the courtroom — but the ruins of a man who lived his life for the law, if not also the legal apparatus itself.

In its lean two-hour runtime, Alan J. Pakula’s 1990 adaptation of “Presumed Innocent” makes a number of incisive points about the American judicial system. First and foremost, it questions whether a courtroom is where truth is ascertained, or merely where various facts are tossed about until a version of the truth satisfies the controlling parties. (Roger Ebert clocked pessimism from the film’s opening shot, which, paired with Harrison Ford’s glum voiceover, suggests a pervasive hopelessness for all involved. “As he speaks of the duty of the law to separate the guilty from the innocent, there is little faith in his voice that the task can be done with any degree of certainty.”)

Each fallible, failing step in the process of trying a man for murder is given enough of a nudge to amplify the viewer’s unease, be it ingrained biases of supposedly neutral adjudicators, political influences dictating an individual’s freedom, or the sexist assumptions inherent to yet another patriarchal American institution. What’s left, in the end, isn’t just a climactic verdict for the accused — and a juicy reveal outside the courtroom — but the ruins of a man who lived his life for the law, if not also the legal apparatus itsel

In the seven bloated episodes screened for critics (out of eight total), David E. Kelley‘s 2024 adaptation of “Presumed Innocent” has yet to examine any such ideas. Yes, there holes aplenty in the prosecution of Rusty Sabich (Jake Gyllenhaal), but ruptures in legal procedure aren’t the show’s focus. There are even lines like, “Trials often come down to storytelling — the best version wins,” but they’re said without a hint of criticism for how the pursuit of justice has been turned into a reality-competition series. Instead, the Apple TV+ murder-mystery is wholly dedicated to two questions: “Did Rusty kill his mistress?” and, “If not, who did?”

As escapist summer fare, it’s diverting enough — especially given the A-list cast enlisted by Emmy-winning casting director Jeanie Bacharach — and Kelley’s time-tested expertise in legal thrillers keeps the pace quick and the patter flashy. But the TV remake of “Presumed Innocent” (officially an update of Scott Turow’s 1987 novel) makes some desperate gambits to fill out its episodes, and the emptiness underneath its dedicated performances proves just as nagging as the monotonous repetition of the same two queries, hour after hour, all the way through the finale (which was not screened for critics). “Whodunnit” is a tried-and-true starting point, but even bawdy beach reads tend to have more to chew on than this.

To its credit, Kelley’s edition of “Presumed Innocent” wastes little time getting to the case at hand. As his wife, Barbara (Ruth Negga) and kids relax in the backyard, Chicago’s chief deputy prosecutor Rusty Sabich gets a call that his co-worker and fellow lawyer, Carolyn Polhemus (Renate Reinsve), has been murdered. He rushes to her house, where his pallid boss, district attorney Raymond Horgan (Bill Camp), warns him that the scene inside isn’t pretty. Indeed, it isn’t. Like too many crime shows about men avenging the death of a woman, Carolyn’s corpse is displayed in the middle of the living room: naked, tied up, and brutally beaten. Forensic workers do their job, and soon, Rusty begins with his: investigating the case alongside Chicago’s finest (although the latter’s presence is downplayed to such an extent you may forget Rusty isn’t a detective).

Unlike the film, his official inquest doesn’t last long. By the end of Episode 1, Horgan loses his bid for re-election and gets supplanted by Nico Della Guardia (O-T Fagbenle), who in turn tosses out Rusty in favor of his preferred deputy counsel, Tommy Molto (Peter Sarsgaard). To say there’s no love lost between each duo would be like saying the North and South sides live in blissful harmony. Kelley amps up the inter-office tensions as high as they can go, so when Rusty becomes a suspect in Carolyn’s murder, all attorneys present are adequately incensed.

Sarsgaard is right at home as the smarmy second-fiddle who flaunts his newly inherited powers yet can’t escape the feeling that he’s not good enough for the post, but it’s Camp who steals every quarrel, consultation, and cutaway shot, his haggard swagger undeterred by defeat, his crisp name-calling a treat every time a “fuckhead” flies from his mouth. (Even Horgan’s extraneous scenes at home merit inclusion by the simple yet brilliant choice to cast Camp and Elizabeth Marvel, who are married in real life, as Mr. and Mrs. Horgan.)

Once Rusty’s affair with the deceased comes to light, it’s a race between the defense — who’s desperately looking for other suspects — and the prosecution, as they stack up circumstantial evidence against their former colleague. Here, Kelley does put a slight emphasis on the burden of proof, aka the state’s responsibility to prove Rusty is the killer beyond a reasonable doubt. The show makes it clear (in its perpetually gloomy, blue-and-brown tinted vision of Chicago) that his best chance at avoiding the death penalty isn’t by finding out who really did it, but reminding the jury that there’s no concrete proof he’s the killer. He’s innocent until proven guilty, and no matter how tempting it is to make assumptions based on probability, that’s not how a jury trial is supposed to work.

Kelley, given his bonafides in courtroom dramas, may have been better off exploring the split between our justice system’s intentions and its actual application. (Anyone who’s sat on a jury, any jury, knows just how… subjective they can be.) But doing so would’ve meant sacrificing one of the many flashy speeches, heated cross-examinations, and shocking (but shallow) episode cliffhangers. “Presumed Innocent” is too often a paint-by-numbers legal procedural, with twists that do a better job filling time than they do deepening the story. Gyllenhaal leans on his trademark intensity to hold our attention, but his emotionally transparent interpretation of Rusty is far less intriguing than Ford’s pent-up exasperation. The latter makes you ask what he’s hiding behind that Midwestern mask of repressed feelings, while the former only lets you wonder whether his oft-justified bursts of violence could also indicate a darker, murderous rage.

For as good as the original adaptation of Turow’s tawdry page-turner remains, there are still enough nagging shortcomings to warrant an attentive remake — especially one smart enough to cast two brilliant actors like Ruth Negga (“Loving”) and Renate Reinsve (“The Worst Person in the World”) in roles that were woefully underdeveloped in the movie. (Then, their characters were victims of a male gaze motivated mainly, it seems, by the era’s growing fear of what would happen to men with so many women entering the workforce.) Alas, this version is only a touch more truthful to Barbara, and exactly as indifferent toward Carolyn. Their characters are largely or completely tied up in Rusty’s story, despite the best efforts of the talented thespians driving them. (Negga, in particular, adds quite a bit, while Reinsve barely has enough dialogue to establish her passable American accent.)

Perhaps the last act will appropriately flesh them out (rather than flash their bare flesh in many-a-sex-scene shared with Gyllenhaal), but the show’s controlling parties don’t seem all that interested in a truth outside the verdict. Merely answering the recurring question — “Who dun it?!” — seems honest enough for them. If the same goes for you, dear reader, enjoy your summer escape. But if anyone should know there’s always more to the matter than what comes out in court, it’s an attorney.